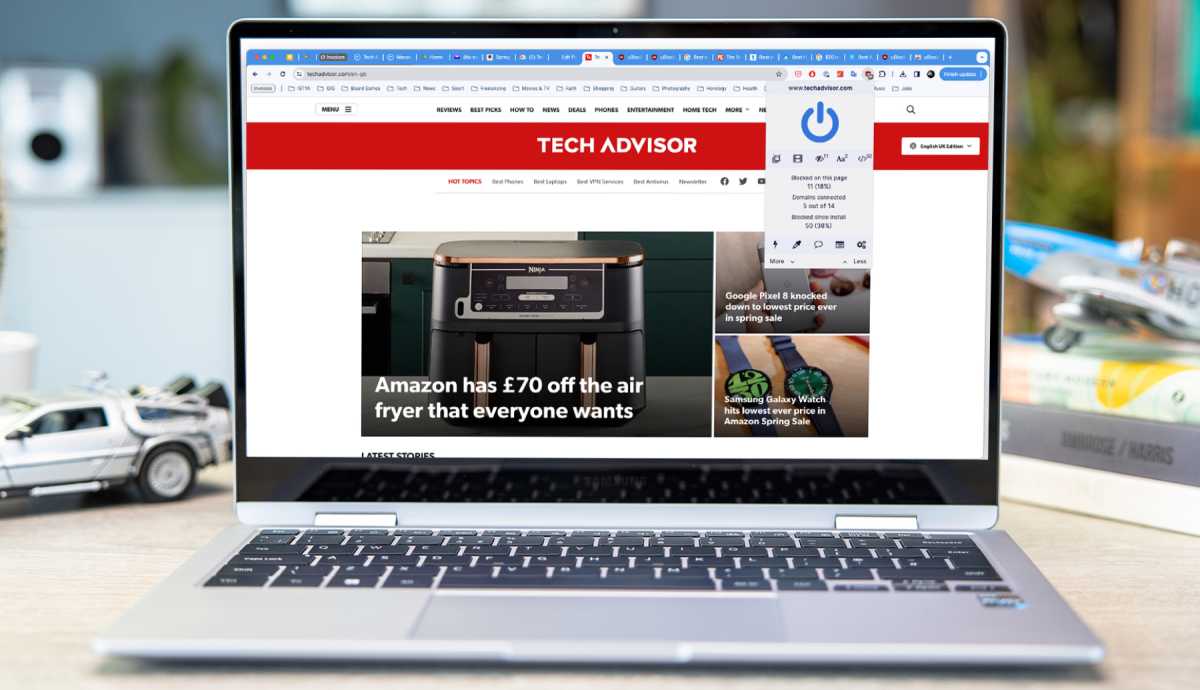

I’ve written a lot about ad blockers in the last few weeks, from Google’s Chrome updates making some popular options inoperable, to alternatives that will work, to my reason for blocking every ad on YouTube. So when I was contacted by representatives from Ghostery, a German company that operates an ad-blocker extension and other privacy products, I was eager to pick their brains.

I’ve been a technology writer for over 10 years, and I can wax poetic on building PCs and keyboards all day. But I’m not a web developer or programmer of any kind, so I relished the opportunity to get an expert opinion on the changes in Chrome’s extension support, from Manifest V2 to V3. The V3 changeover, and its more restrictive access model to some of the browser’s most important internal functions, is the big reason that uBlock Origin won’t be compatible with Chrome and Chromium browsers soon.

What’s changing in Chrome’s Manifest V3

Ghostery

Ghostery

<div class="scrim" style="background-color: #fff" aria-hidden="true"></div>

</div></figure><p class="imageCredit">Ghostery</p></div>Ghostery let me speak with Krzysztof Modras, the director of engineering and product, and company CEO Jean-Paul Schmetz. And the first thing I asked was, what’s the big difference in the Manifest V3 extension support that’s causing all these issues for ad blockers?

“The most important limitation of Manifest V3 is the removal of extension access to the browser’s network layer,” Modras said. “The enforcement of this declarative approach disables advanced on-device protection and in turn will significantly limit innovation in the privacy space. Extensions will lose important tools and permissions that have previously allowed them to quickly react to new threats directly from the user device.”

“[Google said] the goal was to improve privacy, but that never actually happened,” said Schmetz. Because effective extensions compliant with Manifest V3 will need to request access to every single website — something that UBlock Origin Lite does in order to work on the new standard — users could become complacent with these requests, and make themselves more vulnerable to rogue actions.

Martyn Casserly

<div class="lightbox-image-container foundry-lightbox"><div class="extendedBlock-wrapper block-coreImage undefined"><figure class="wp-block-image size-large enlarged-image"><img decoding="async" data-wp-bind--src="selectors.core.image.enlargedImgSrc" data-wp-style--object-fit="selectors.core.image.lightboxObjectFit" src="" alt="uBlock Ultimate ad blocker" class="wp-image-2276162" width="1200" height="691" loading="lazy" /></figure><p class="imageCredit">Martyn Casserly</p></div> </div></figure><p class="imageCredit">Martyn Casserly</p></div>Modras pointed out that, while ad-blocking extensions can’t directly modify network requests, other extensions can still get access to user data. So locking access to the layer without fully locking it down is creating a potential security vulnerability: Rogue extensions can continue to abuse other permissions to monitor and potentially relay all that data, even though ad-blocking extensions can’t modify or block it for the user.

“Google’s approach to extensions in the browser appears to be limiting them to be as single-purpose as possible,” said Schmetz, “ideally working on just one website. So serious tools will need to request ‘wide host permissions’ that come with ‘scary’ security messages about access to ‘usernames and passwords.'”

Manifest V3 has other restrictions that make ad blocking harder, including limits for static and dynamic rules. The immediate effect users will see is that updates to ad-blocking lists will come slower, and some pages that experienced breakage won’t be fixed as fast as under Manifest V2.

Schmetz believes that Google sees user-installable extensions as a detriment to Chrome as a browser and a platform, at least from its perspective as a company focused on advertising and user data. When Chrome launched in 2008, its biggest competition was Firefox, so extension support was a must-have feature. But Schmetz points out that the Android version of Chrome still has no browser extension capabilities years later, even though Firefox on Android has had this for quite a while.

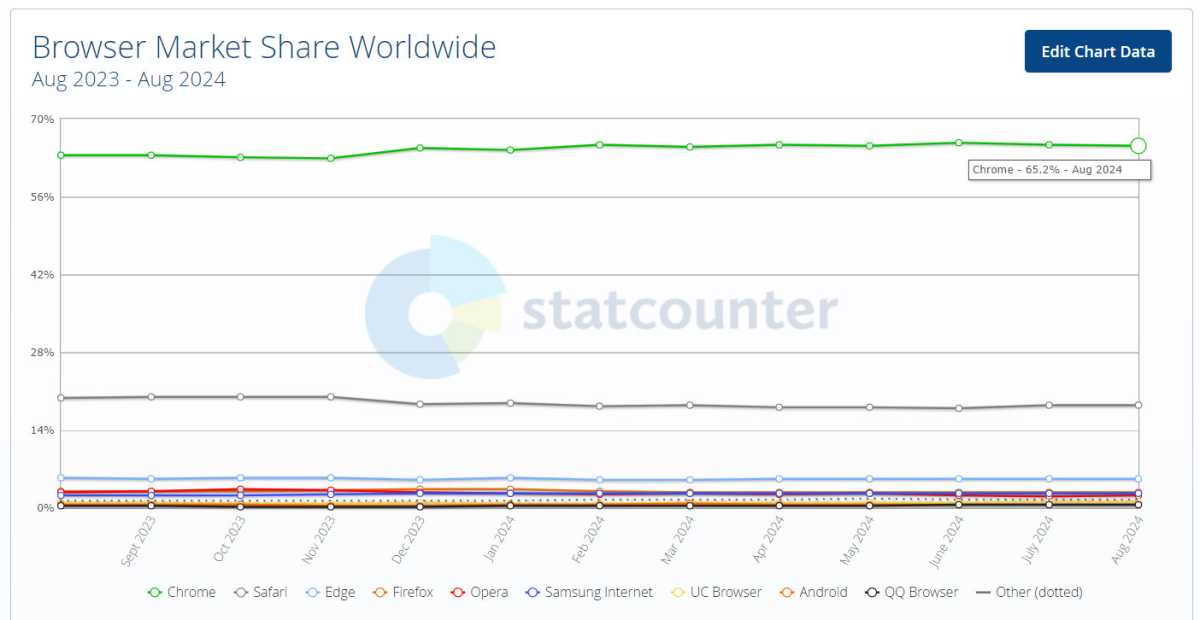

<div class="lightbox-image-container foundry-lightbox"><div class="extendedBlock-wrapper block-coreImage undefined"><figure class="wp-block-image size-large enlarged-image"><img decoding="async" data-wp-bind--src="selectors.core.image.enlargedImgSrc" data-wp-style--object-fit="selectors.core.image.lightboxObjectFit" src="" alt="stat counter browser market share" class="wp-image-2460686" width="1200" height="621" loading="lazy" /></figure><a href="https://gs.statcounter.com/browser-market-share/desktop/worldwide" target="_blank" class="imageCredit" rel="noopener">StatCounter</a></div> </div></figure><a href="https://gs.statcounter.com/browser-market-share/desktop/worldwide" target="_blank" class="imageCredit" rel="noopener">StatCounter</a></div>Chrome is currently the #1 browser in the world, with 65 percent of the market on both desktop and mobile. Edge, also based on Chromium, is a distant second on desktop, with Apple’s Safari at about 25 percent on mobile.

Is Google intentionally hampering ad blockers?

On the subject of Google’s intentions as the maintainer of Chrome, I decided to be blunt. “Do you think Google made the Manifest V3 changes to protect its advertising interests and leverage Chrome’s market share?” I asked.

“The true answer to that is that Google is probably too complicated as an organization to do that efficiently,” said Schmetz. “What is absolutely clear is that they tried to make Chrome a more predictable platform, because Chrome for them is a very important platform for the rest of their monopolies.

“One of the first uses of extensions on Chrome was to change the default search engine. Ghostery is about making sure Chrome isn’t leaking data left and right, as well as blocking ads. Google has its own analytics services, which we block.

“From the perspective of Google, no extension makes Chrome better, for the user, for Google, for Google’s customers. But I don’t think [Google CEO] Pichai said ‘we’ve gotta kill extensions for our ad business,’ not at all.”

Melden Sie sich an, um einen Kommentar hinzuzufügen

Andere Beiträge in dieser Gruppe

RealSense, a depth-camera technology that basically disappeared withi

These days, the pre-leaving checklist goes: “phone, keys, wallet, pow

One of the most frustrating things about owning a Windows PC is when

Every now and then, you hear strange stories of people trying to tric

Cars are computers too, especially any car made in the last decade or

Cropping images on Windows is easier than you think, thanks to built-