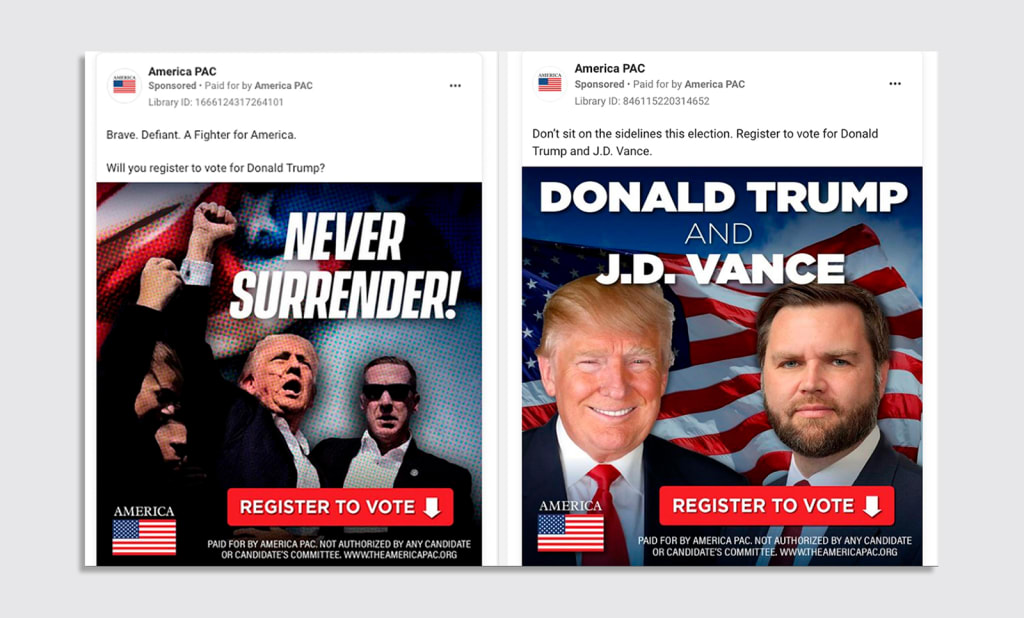

The ads swept across Facebook and Instagram feeds last month, mostly in battleground states, just three days after the attempted assassination on Donald Trump. Above a now iconic image of the former president raising his fist, “Never Surrender!” and “Stand with Donald Trump!” they declared. Below Trump, large red banners beckoned people to register to vote.

The nearly $900,000 ad blitz was paid for by America PAC, the Elon Musk-backed super political action committee that’s helping the Trump campaign register and mobilize the electorate in battleground states. Musk himself reportedly has taken a hands-on role in the group’s operations, which are aimed at turning out some 800,000 swayable voters in an election that will likely hinge on small margins.

Besides Musk—who has reportedly suggested he would donate $45 million per month to the group—America PAC’s official backers include Joe Lonsdale, a venture capitalist and Palantir cofounder, and cryptocurrency investors Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss. Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, who run one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent venture capital firms, also plan to back America PAC, The Information reported.

Musk’s involvement has drawn the most attention, which isn’t surprising given the X owner’s outsized influence and tendency toward drama. But to campaign watchers, it’s the PAC’s tactics to reach voters that are raising more immediate questions about privacy, transparency, and election integrity.

Much of the group’s online voter registration drive relied on forms that collected voters’ personal data within Facebook and Instagram but which do not appear in Meta’s ad library, Fast Company found. After a sudden overhaul last month, the PAC has since resumed its data-driven voter operation, which, thanks to newly loosened laws, can now be directly coordinated with the Trump campaign.

“It is appalling that Elon Musk’s super PAC plans to mine voters’ data under the false pretense of helping them register to vote, and then use that data for on-the-ground voter canvassing directly coordinated with Donald Trump’s presidential campaign,” says Saurav Ghosh, director of federal campaign finance reform at the nonprofit watchdog Campaign Legal Center.

While many super PAC activities fall under the scope of the Federal Election Commission, voter registration drives like America PAC’s are largely governed by state laws, which place restrictions on how people’s data is collected and used. Democratic officials in North Carolina and Michigan briefly considered investigating the PAC’s activities but, after receiving assurances from PAC lawyers, officials told NBC News that they would continue to monitor the group instead.

Thessalia Merivaki, an associate professor at Georgetown University who studies voter access, says that, legal implications aside, America PAC’s voter registration ads seemed “a bit deceptive.”

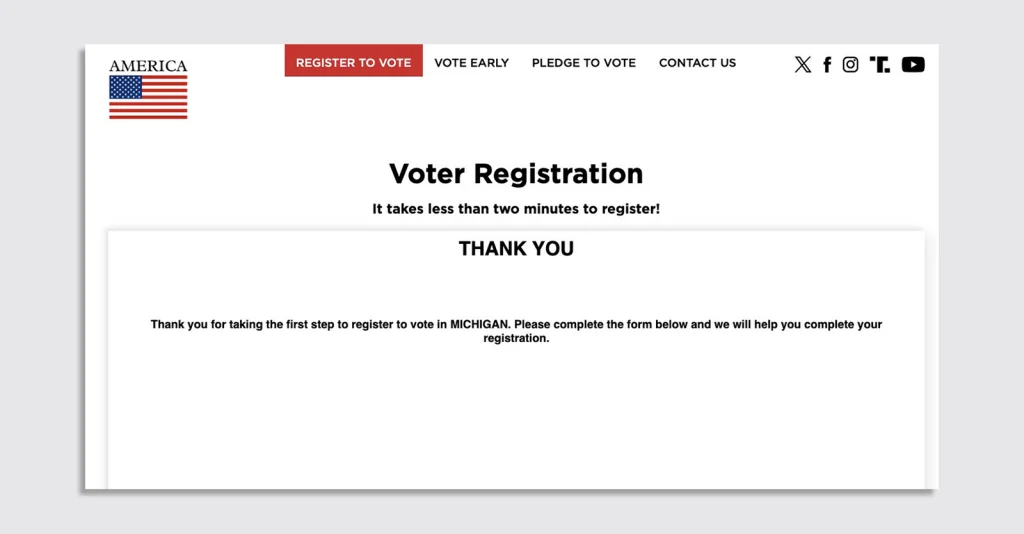

Online voter drives are not uncommon, she noted, but America PAC’s process could mislead people into thinking they’re filling out actual voter registration forms, potentially discouraging them from filling out the real paperwork when it shows up in the mail. “If a voter experiences that, and then they don’t get to vote, that will affect how they trust the process, and that’s a major issue,” says Merikavi. A digital voter registration effort “could have been well-intentioned, but the outcome can leave a bad taste.”

Meta’s vanishing forms

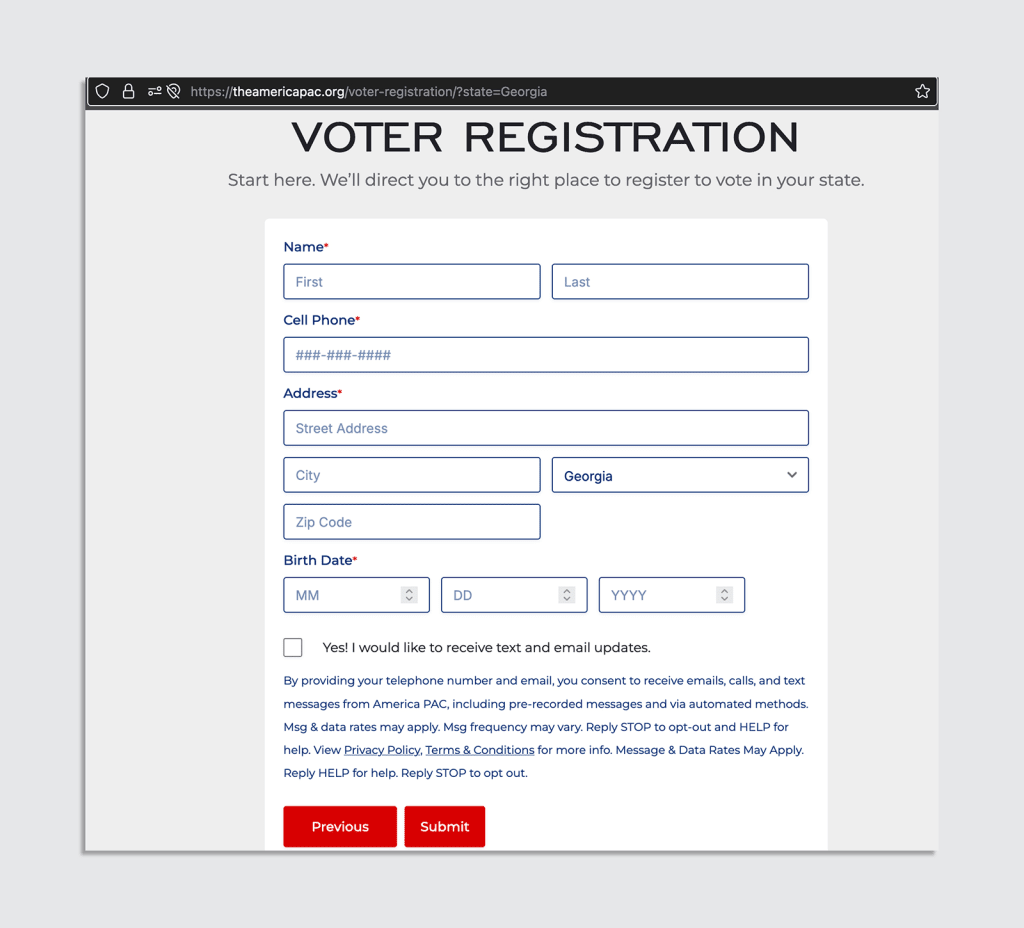

Part of the PAC’s efforts revolved around encouraging people to enter their personal data on its website. Visitors who clicked on Google and ">YouTube ads last month were led to a landing page with a form that asked for their email and zip code. But, as CNBC reported earlier this month, a visitor indicating that they lived in a swing state was presented not with a link to their official voter registration portal but to another form that requested their name, address, and phone number. The site did not ultimately direct these people to an official voter registration page.

On Facebook and Instagram, however, the ads were different. Users who clicked weren’t taken to the PAC’s website; instead, they were shown a pop-up form within their feeds asking for their personal information. Afterwards, they were also not directed to their state’s official voter registration portals.

What data the forms on Meta gathered, what disclaimers they contained, and what specifically they showed users upon completion is unclear. Meta declined to share the forms, and representatives for America PAC did not respond to requests for comment.

But according to Meta’s Ad Library, the campaign was intense: For about two weeks in July, the PAC paid Meta $899,458 to show dozens of variations of these ads, mostly to audiences in the battleground states of Arizona, Michigan, Georgia, North Carolina, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. That made America PAC the tenth biggest political advertiser on Meta’s platforms last month, and the second biggest Republican spender after the Trump National Committee Joint Fundraising Committee. The ads were shown on 14.7 million screens, according to the ElectionGraph project at Syracuse University.

By contrast, America PAC spent only about $20,000 on the “register to vote” YouTube and Google ads that sent users to America PAC’s website. Unlike Meta, Google does not permit form ads, also known as lead ads or lead forms, for political content. (“In line with our standard practices, we restrict sensitive ad categories from using this format,” a Google spokesperson explained. “This format is also restricted in other sensitive ad categories including ads related to gambling, alcohol, and health care and medicine.”)

The use of the “voter registration” pop-up forms on Facebook and Instagram, which has not been previously reported, flew farther under the radar than the conventional ad campaign on Google. While the ads are archived, the forms themselves do not appear in Meta’s Ad Library, which the company created after 2016 to provide more transparency into electioneering on its platforms. Clicking on most of the ads in the Ad Library simply redirects users to Facebook’s homepage.

After a series of calls and emails, a representative for Meta confirmed that the ads actually “pop up a form in feed for users to fill out.” But Meta declined to share the forms or answer any questions about them, including what disclaimers they contained or what users saw after filling them out.

Meta says it is committed to election transparency and dedicated to “empowering people to vote.” On one page, the company touts its Ads Library “so you can see exactly what candidates are saying, who they’re targeting, and who paid for it,” and points to its voter engagement efforts, including in-app notifications, which are “continuing to connect people with details about voter registration and elections.”

With regard to America PAC’s ad campaign, however, Erin Logan, a Meta spokesperson, said in a text message, “We have nothing more to add here.”

“Pretty sketchy”

State officials and nonpartisan groups increasingly use websites, in addition to paper mailers, to help voters get registered, which is required to vote in all states except North Dakota. Political parties, meanwhile, have been running voter drives since voter registries began; the web supercharges the ability of partisan groups to leverage all that voter data for electioneering purposes. Typically, all of these websites redirect visitors to official state registrar pages, where they can complete their registrations. Some, like Rock the Vote, are even directly integrated with a number of state voter systems.

Typically, digital ads draw prospective voters to these websites. It’s far less common to see form ads used for political purposes, and especially in voter drives.

From a campaign standpoint, says one Republican strategist who asked not to be named, it looks “pretty sketchy to use FB lead-gen forms if you’re telling people it’s registering them to vote . . . and then you don’t actually follow through.”

In letters to officials in Michigan and North Carolina on August 7, lawyers for the PAC, Chris Gober and Charlie Spies, said it was acting in good faith and “is utilizing the data it collects to register voters and encourage them to vote.

“Admittedly, not all our plans or strategies are public at this time, but any investigation into our efforts will prove premature and imprudent,” the lawyers wrote.

The Meta and Google ads were the tip of the spear in America PAC’s digital efforts to gather data from voters and prospective voters. Once audiences in battleground states provided their info online, PAC employees would use the data to fill out voter registration forms, which they then mailed to the prospective voters to sign and send in by mail, according to sources who spoke with the Wall Street Journal. The personal data is also useful for targeting visitors with ads and texts, and can be enriched with other voter databases for more precise on-the-ground mobilization efforts.

Late last month, around the time the Meta and Google ads stopped, Musk approved the sudden shake-up of the PAC, firing its Austin-based digital ads firm Raconteur Media and its canvassing contractor In Field Strategies. It isn’t clear what led to the overhaul, which was first reported by the New York Times.

By the time it was fired, the Journal reported, digital contractor Raconteur Media told the PAC’s leadership it had compiled voter registration forms for about 8,500 people from swing states who provided their information “through the website.” (It’s not clear if that number included voter data gathered through Facebook and Instagram.) Before Raconteur could send out the forms it had assembled, however, it was fired. In early August, America PAC temporarily rehired the firm in order to mail the 8,500 forms, the Journal reported.

Meanwhile, In Field Strategies, the canvassing firm, said it had helped register approximately 4,000 people, knocked on 725,000 doors, and got 26,000 absentee commitments.

Why use form ads to gather people’s contact information for a voter registration drive? Lead ads or form ads can be easier for users to fill out than a form on an external website, resulting in more of the “leads” advertisers use to follow up with emails and texts. But form ads are also thought to produce low-quality leads, and provide less control, than a landing page.

They also don’t allow advertisers to direct users to a donation page, says Eric Wilson, a political technologist who led Marco Rubio’s digital team during his 2016 presidential campaign. Or, for that matter, an official voter registration page.

There is a more immediate risk to voter trust too, especially if the Meta form ads did not immediately direct voters to an official state portal, says Merivaki. Form ad “thank you” pages can only display text and a URL. “If you say this is how you register to vote, but there’s no path to clearly transition from the website to the election authority who is the only authority that can register someone to vote, then that’s clear deception,” she says.

Katie Harbath, who was previously director of public policy for global elections at Facebook, said the use of form ads here was surprising, partly because using a landing page allows for more control, including A/B testing. But the implications of collecting voters’ contact info through Meta—which technically owns the data entered into its form ads—were more eye-opening.

Login to add comment

Other posts in this group

One recent rainy afternoon, I found myself in an unexpected role—philosophy teacher to a machine. I was explaining the story of the Bha

The Minecraft movie is crass, dumb, and barely coherent. It also just made almost $163 million at the domestic box office over its opening weekend.

Video game adaptations have

Camb.ai is on a mission to disrupt the dominance of English in global media. Founded in 2022, the AI-powered platform specializes in real-time translation that retains a speaker’s emotional resona

Founders and CEOs typically use social media to etch a human face onto their brand, forge a personal connection with potential customers, and put some pizzazz into product launches.

With

Tesla starts selling cars in Saudi Arabia on Thursd

Cars are about to get a lot more expensive. This startup wants to make your