This article is republished with permission from Blood in the Machine, a newsletter about AI, Silicon Valley, labor, and power. Subscribe here.

Halloween is upon us, which means it’s a good excuse to watch some films from one of cinema’s most under appreciated genres: science fiction horror.

As I argued years ago, it’s a shame that there’s something of a dearth of this stuff. Hollywood is reluctant to touch it, which makes sense, since sci-fi usually wants a big budget, while most horror films, by virtue of being horror films, automatically limit their prospective audiences. Fortunately, sci-fi horror still gets greenlit in tinseltown from time to time, and independent studios and directors find ways to make it work—and when it works, it really works.

Not just because filmmakers can really push aesthetic and tonal boundaries here—this is the prime playground for Cronenbergian body horror and J-horror—but because it’s one of the most effective mediums in which to register a critique of tech and its corporate masters. To express technological anxieties and convey injustices on visceral level that even, say, reading brilliant blog posts by tech journalists can’t match. Especially in the sub-subgenre of sci-fi horror that tackles tech, which is sometimes called “techno-horror,” though I tend to resist this term, as it sounds a bit too much like something that might happen at a Skrillex concert. I prefer ‘luddite horror.’

As regular readers of my newsletter know, the real Luddites were not dumb reactionaries who wanted to smash machines because they did not understand them. They were a well-organized and militant labor movement whose members fully grasped the threat certain machines posed to their livelihoods, when used by factory bosses to drive down wages and exploit child labor. The Luddites had a furious critique of technology, and they also knew that if it was being used to oppress or exploit, sometimes the moral thing to do was to destroy it.

Sci-fi horror is a genre particularly adept at channeling such moral rage, and expressing that gut feeling of dread and injustice that textual critique simply can’t reach, especially not at scale. It’s one thing to say ‘corporate AI can be dangerous’ and it’s another to forever imagine the foot of a T-800 crushing a human skull. And while plenty such films are blunt and effectively appeal to our lizard brains, lots of luddite horror films have sharp, even nuanced critiques of tech, too.

So, as I was pulling myself out of a stupor, and avoiding social media like the plague, lest my blood pressure spike and induce another trip to the bathroom, I assembled this list of essential luddite horror films; films that challenge, critique, or otherwise set out to smash the machinery hurtful to commonality. They range from classics you’ve probably already seen a few times to the obscure and occasionally grotesque and obscene. Since we’re talking luddite horror here, some of the all-time classics in the sci-fi horror genre won’t make an appearance—sci-fi horror films like The Thing, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and The Platform have plenty of critical meat on their bones, but their chief targets aren’t tech. And I’m sure I’ve missed some, so do leave your favorites in the comments—and this Halloween, add some machine-breaking to your horror mix.

‘Event Horizon’ (1997)

Arguably the gold standard for horror films set in space whose titles don’t rhyme with mammalian, if only because the competition for said category is mostly limited to shark-jumping Leprechaun and ">Friday the 13th sequels. Event Horizon, famous both for flopping upon release and for ">that scene where they watch the tapes of the ship’s last crew tearing out their eyeballs and doing other such student film violence to each other, also happens to carry one of the biggest and bluntest “man should not mindlessly meddle with technology” messages in horror.

This is because Event Horizon is essentially a Frankenstein movie that takes place in Neptune’s orbit, with the entire hell-traversing, semi-sentient titular spaceship taking on the role of the Monster, and Sam Neil’s Dr. Weir character and a behind-the-scenes U.S. government sitting in for Dr. Frankenstein. See, Weir designed the Event to bend the laws of spacetime itself, and wound up opening a portal to hell—maximum Frankenstein, you could say, in terms of reckless sowing and humanity reaping. What makes this a good Luddite horror film is that our chief protagonist, Laurence Fishburne’s Captain Miller, takes one look those tapes and makes the correct moral decision to fire every missile he can at the Event Horizon. Weir, even before he gets possessed by the ship/demon, is dedicated to trying to salvage the hell portal. Fortunately, Miller succeeds in destroying Weir and most of the ship, potentially sending them all to hell in the process. But the final scene, in which one of the survivors has a vision of Weir returning, indicates that this impulse, to construct devices that could literally unleash hell on our world, has survived after all.

Double feature: Hellraiser (1987). Okay, it’s kind of a stretch to call Hellraiser sci-fi, but it does feature a device, the Lament Configuration, that when opened promises to deliver its users levels of pain and pleasure that transcend the earthly plane. And it implicitly contains the idea that people who seek it out will suffer an eternity of hell and pain and should maybe not do that.

‘Invisible Man’ (2020)

Invisible Man is a lowkey great horror film that shrewdly recalibrates a classic franchise to execute a loaded satire of tech CEOs, toxic masculinity, and (literally) invasive technologies. This is how reboots should be done, in other words. If its reign wasn’t cut short by the 2020 pandemic dead year for the film industry, I bet its cultural imprint would be oh twice as big. It’s top tier mainstream horror, expertly constructed, and also contains what is for my money one of the most ‘holy shit’ scenes of the decade so far.

Elisabeth Moss’s Cecilia Kass is married to Adrian Griffin, an abusive, domineering tech CEO; she escapes their surveillance fortress of a home, then news breaks that Griffin has committed suicide, and then an invisible presence begins tormenting her everywhere she goes. The film drew praise for Moss’s performance and the way it channelled the fear, PTSD, and gaslighting abuse victims endure every day, and it’s just as effective at skewering tech titans. Griffin uses his vast wealth and cutting edge “human augmentation” tech to surveil and torment his ex, prompting we viewers to interrogate why such things are built and for whom. Better yet is the ending, in which the CEO tries to evade accountability for his crimes—his invisible man technology gives him plausible deniability—and Kass responds by taking matters into her own hands.

Double feature: Upgrade (2018) Director Leigh Whannell’s previous feature also rules; it’s more of a violent revenge thriller than horror I guess, but it similarly puts a malevolent tech titan in its crosshairs, and raises some questions about who AI is serving in the process.

‘Ringu’ (1998)

Some four hundred years ago when the Ring movies were a pop culture phenomenon and I was a teenager, I remember everyone being more fixated on the haunted ritual that provides the primary plot mechanic—watch the cursed video, and you’re dead in a week—and the scary visuals, and less on the cutting critique of media technologies that sits at its core. Which is fair, it’s a great hook, a killer updating of the Bloody Mary myth, and who knows, I was a teenager, it is possible I missed some of the critical dialogue taking place at the time. But what struck me on rewatching these films more recently is how directly they transmit the theme that new technologies are bound to replicate the traumas of the past—only more violently, and more frighteningly, because our new technologies are ubiquitous. Every TV holds the potential of beaming in death, every ringing telephone a distant threat of violence. The source of the destruction—the recorded anguish of an abused, disturbed and malevolent child—is more resonant than ever; the kind of darkness that, real or imagined, animates the more harrowing corners of the curdled online media ecosystem.

Ringu in particular holds up, at least for those who retain the social context of VCRs and corded phones, even more so than the American remake. 2002’s The Ring is, naturally, blunter and more interested in leaning on stock horror imagery and generating jump scares, but is still nonetheless pretty solid. One difference I noticed; both films have a scene where the protagonist—a journalist and single mother in both—steps out onto the balcony of her sprawling apartment complex while her ex watches the cursed short. In Ringu, she considers the industrial sprawl, and the transmission infrastructure capable of beaming in such horror; in the Ring, she looks at all the TVs that are on in her neighbors’ apartments. The final twist, that the only way to escape the video’s curse is to copy it, today feels like a pitch black punchline—the way we survive is to grease the wheels, to share the cursed content; you know, to help it go viral.

Double feature: The Ring (2002). It’s still fun and well made, if distinctly hokier—try not to cringe as Naomi Watts makes her entrance, announcing herself as a hard-charging journalist by telling her editor to keep his hands off her column. But the jump scares that replace Ringu’s brooding dread are pretty good, actually.

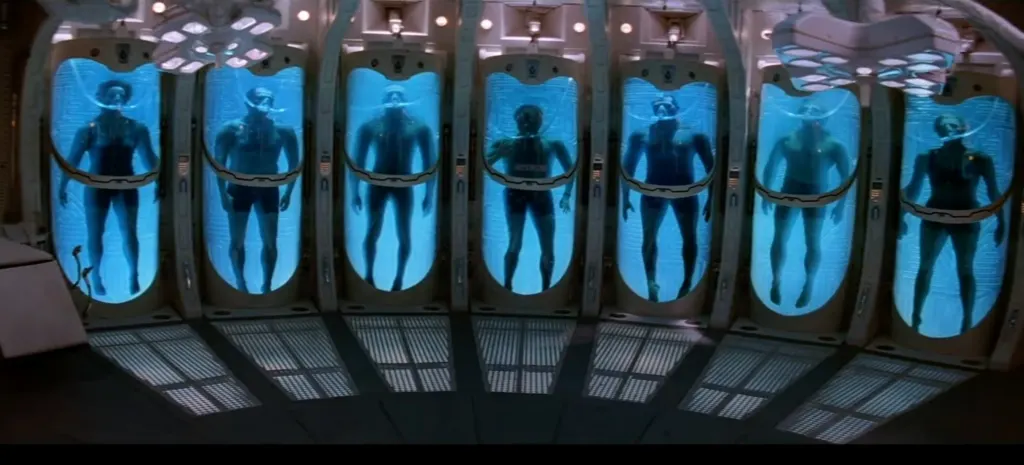

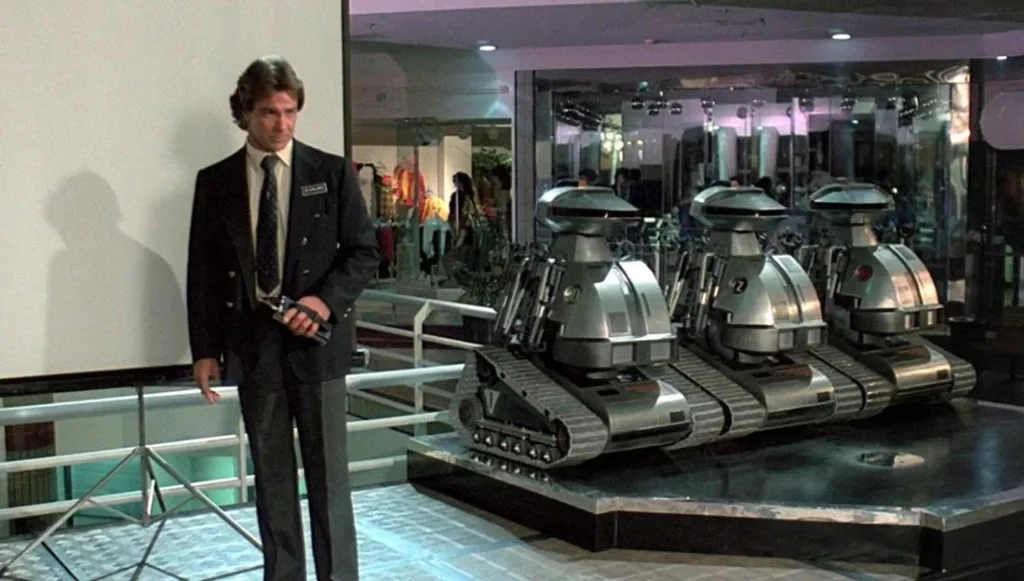

‘Chopping Mall’ (1986)

We have to have at least one ridiculous, deep B-movie horror film on this list, right? Part RoboCop-esque Reagan-era consumerist satire, part cheap 80s slasher flick, and part Short Circuit minus Steve Gutenberg, the misleadingly titled Chopping Mall more than fits the bill. A mall adopts a high-tech security system designed to stop shoplifters, led by three armed “Protector” robots; it goes haywire and starts misidentifying teenagers partying at the mall after hours as intruders and killing them. It’s campy, self-aware, and is essentially an extended screed against privatized security tech loaded with cartoonish violence. It also gets bonus points for including the very Luddite line, “Computer huh? Let’s go trash the fucker,” uttered when the teens set off to destroy the central surveillance system controlling the killer robots.

Double feature: Dawn of the Dead (1978). Perhaps obviously, Romero’s sequel to Night of the Living Dead is by far the superior film, and its satire of consumerism is funnier and more pointed, but I don’t think it quite qualifies it as luddite horror, unless you consider the mall itself a technology, which—the case could be made!

‘Threads’ (1984)

Ah Threads. Let’s just come out with it: This is one of the bleakest and most viscerally affecting movies you will ever watch. It’s less a “horror film” and more just “horrific,” and that is because it attempts to methodically render, step by step, day by day, what a real-life nuclear holocaust would look like when the bombs started to fall.

Set in the thick of the Cold War, the nuclear powers snap, and the target is Sheffield. So you see the bodies vaporized by the blast radius, the horribly burned further out, the crazed and irradiated drive to survive among those left, sifting through the wreckage, dying from radiation poisoning, or ultimately freezing through the eventual nuclear winter. It’s not a found footage film, but the effect is like watching a documentary of a future that was and is always a few presses of a button away. That’s what makes it so vital—it forces you to inhabit such a future. If more people did, we might feel better about our chances of it never coming to pass.

Double feature: Mad Max (1979). Too much its own beast to be considered horror, the first Mad Max, often overshadowed by its higher octane siblings, presents a uniquely queasy and unsettling vision of the onset of the apocalypse.

Login to add comment

Other posts in this group

Yahoo’s bet on creator-led content appears to be paying off. Yahoo Creators, the media company’s publishing platform for creators, had its most lucrative month yet in June.

Launched in M

From being the face of memestock mania to going viral for inadvertently stapling the screens of brand-new video game consoles, GameStop is no stranger to infamy.

Last month, during the m

The technology industry has always adored its improbably audacious goals and their associated buzzwords. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg is among the most enamored. After all, the name “Meta” is the resi

Even as AI becomes a common workplace tool, its use in

Finding a job is hard right now. To cope, Gen Zers are documenting the reality of unemployment in 2025.

“You look sadder,” one TikTok po

Hiding your address, phone number, and other details is easier than you might think.