College football is suddenly in a constant state of change. The transfer portal, conference realignment, players making millions in NIL deals, the first-ever 12-team playoff—if you cryogenically froze someone five years ago and woke them up today, they wouldn’t recognize the sport.

But one recent experiment has flown largely under the radar.

Outsmarting sign-stealers

After the University of Michigan sign-stealing scandal in 2023, the NCAA approved NFL-style helmet communication for Division I in 2024, allowing coach-to-player audio communication through the helmet of one player on the field. The goal was to reduce reliance on hand signals and oversized play cards from the sideline, which opponents can decipher (or steal) and use as a competitive advantage.

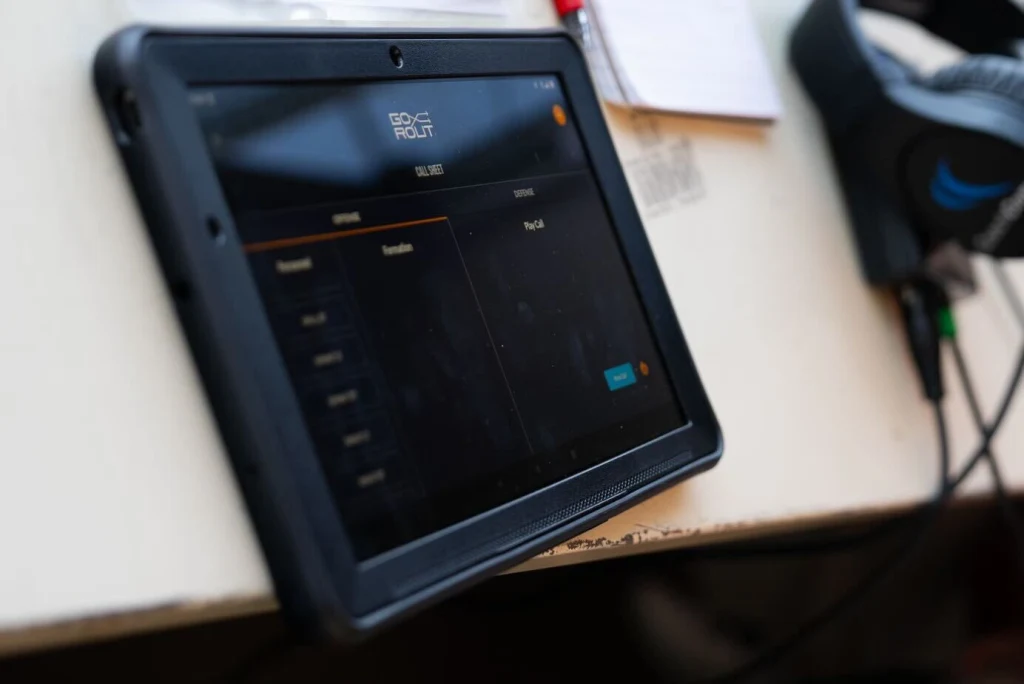

As part of the same initiative, the NCAA also granted the Liberty League, a seven-team conference in New York State, a waiver to pilot a system from tech company GoRout that provides special tablets for coaches to upload playbooks and send calls directly to players on the field via custom smartwatches. Each team received 10 player devices and two coach tablets for conference play in 2024. Teams could use three devices per team on offense and defense, with no limit on special teams.

The hope was that the technology would simplify communication, making it safer and more efficient. Early returns support that result.

“We’ve seen an uptick in our overall efficiency, and the watch system has allowed us to streamline our communication,” says John Drach, head coach at Union College, which completely abandoned hand signals and relied solely on GoRout’s technology. “It has eliminated stealing of our offensive signs, and this technology eliminates the ‘telephone game.’”

But the true yield from the experiment offers a glimpse into college football’s future—a shift bordering gamification that could transform how offenses and defenses operate, making the on-field product faster and more dynamic than we’ve ever seen.

The light-bulb moment

Before he became the founder and CEO of GoRout, Mike Rolih was driving a limousine in Rochester, Minnesota in 2015 when he learned that one of his old high school football teammates was coaching at a junior college nearby. He attended a few practices.

“When they got to the part of practice where they were getting ready to prep for that week’s opponent, the entire practice went to shit,” he says. He visited some local high school practices and observed similar breakdowns. “I thought, ‘There’s probably something here.’”

The problem teams were facing was that, to prep for the opponent, you need to run the opponent’s plays in practice, and the primary mode of learning those plays was players huddling around a coach holding up a binder.

Rolih was shocked that in the era of iPhones and Bluetooth, coaches still relied on physical playbooks, binders, and signals from the sideline to call plays. He’d contemplate this dichotomy often during the idle hours driving his limo, often discussing his ideas with one of his regular clients: George Fisher, who happened to be the former CEO of Motorola.

During their routine hour-plus drives between the Mayo Clinic and Minneapolis airport, the concept for GoRout began to take shape. Fisher said that if Rolih ever got something off the ground, he’d love to see a prototype.

A deal sealed on the tarmac

So Rolih, who earned a master’s in science and technology from Eastern Illinois University, cobbled together a system using an old Toshiba laptop, a home router, and prepaid phones from Best Buy. He wrote a simple kiosk program for the phones that blocks all other content and uses, turning the device into a dedicated receiver that only displays content sent from a central server. He turned the laptop into that localized server, on which he could load content and, with the push of a button, send it to the phones.

“It was very, very rudimentary,” Rolih says. “But it worked . . . 33% of the time.”

That was enough for Rolih to call Fisher, who—true to his word—flew from Scottsdale, Arizona to see the prototype.

When Fisher’s private jet landed on the tarmac at Rochester’s Signature Airport, Rolih was waiting. He had set up his mish-mash of a prototype on a luggage cart and wheeled it out onto the tarmac, meeting Fisher halfway, his Tinkertoy tethered to the terminal by a 200-foot extension cord.

He fired up the Toshiba, ran the program . . . and it worked.

“How much do you think it’s gonna take to get started?” Rolih recalls Fisher asking.

“I think it’s gonna take $150,000,” Rolih said.

“You’re way off,” Fisher replied. “It’s gonna take at least 300.”

Fisher pulled out his checkbook, cut Rolih a check for $300,000, and GoRout was born.

College football powerhouses

Rolih went to work immediately, developing a beta product in 2016 and taking GoRout to market in 2017. That year, GoRout was among the winners of the NFL’s 1st and Future competition—a Shark Tank-style pitch contest for sports tech startups—winning $50,000.

The company has achieved significant milestones since. It recently closed a $3 million equity round and has raised nearly $8 million in investor capital. It has onboarded 27 college football programs to use its product in practice, including Alabama, Auburn, and Rutgers. And in 2024, the company launched a successful wearable tech product for softball and baseball, which is already used by 140 colleges nationwide.

But the company’s most pivotal moment came in January 2023. That’s when Drew Robinson, GoRout’s chief partnerships officer, received a call from Todd Berry, the executive director of the American Football Coaches Association. The NCAA was exploring implementing NFL-style helmet communications, but they were concerned with cost, equitable access, and the liability associated with altering safety equipment such as helmets. They were looking for a more sensible, scalable alternative.

“We weren’t ready,” says Robinson. “But, of course, we said yes.”

Immediately, Robinson and the GoRout team went to work on its system to get it both game-ready and ready to pitch to the NCAA, which involved a series of hurdles.

First, their original system used regular cell service, which wouldn’t work reliably in large college football stadiums packed with fans on game days. To solve this, they chose to use a CBRS network, a private 5G network that operates on a special frequency band, essentially giving organizations their own personal cell network that’s more reliable than public networks. To maximize efficiency and security, GoRout built one of the first-ever portable CBRS kits to include as part of its package.

Scaling up — and down

However, this created a new problem: Very few devices are compatible with CBRS networks. So, GoRout had to develop custom devices specifically for CBRS use in big stadiums.

But they still faced another key scalability challenge: Smaller colleges in rural areas couldn’t afford this high-end system. So, for these schools, GoRout called on its network partner, KORE Wireless, to create a different solution using a technology called Super SIM, which is effectively a master key that unlocks global access to all major cell networks and dozens of regional ones across the country, providing native connectivity and ensuring reliable service even at smaller, rural venues.

The end result is two different systems: a powerful custom network for major stadiums, and a more affordable solution for smaller schools that works anywhere with cell service.

With the technology refined and ready for game use, in February 2024, the NCAA approved GoRout for experimental use, allowing Division II and III conferences to petition for testing.

GoRout chose Division III’s Liberty League, for one reason only: Union College Head Coach John Drach sits on the NCAA Football Rules Committee, serving alongside Georgia Head Coach Kirby Smart, among others.

“We felt very strongly that we had to have somebody who was going to be in that [rules committee] room experience the in-game product,” Robinson says. “And John was a previous user of our practice product. So it kind of came full circle with him being able to really guide us through the experimentation process.”

GoRout’s freshman season

As with any experiment, the initial implementation strategy was simple, featuring the most basic iteration of the technology’s capability.

Each team received two coaches’ tablets and 10 player devices (smartwatches). Three players on offense and defense were permitted to use the devices, with unlimited use on special teams. The coaches loaded their playbooks onto the tablets and, instead of running in a substitute player to relay the play call or use hand or poster-board signals from the sideline, they could message plays directly to the players on the field via their smartwatches—most often the quarterback and wide receivers on offense and linebackers and safeties on defense.

There were no images, only text that would show up on the screen. This was used for both initial play calls and for audibles and other adjustments at the line of scrimmage. More than 50% of the calls were sent in from the coaches’ box rather than the coach on the sideline (because they have the bird’s-eye view). Six of the seven Liberty League teams used the technology, and the prevailing sentiment was nearly unanimous.

They want more—more devices, more dynamic play-calling abilities, more freedom, more GoRout.

“Our biggest issue with using it on offense is that we only get three [devices],” one coach said. “If we had 11 we would use the technology exclusively.”

A special aid for special teams

Drach’s team used GoRout effectively on special teams, sending out his kicking team for extra points but lining them up in an offensive formation. Once his coaching staff saw how the defense lined up, if they didn’t like what they saw, they’d use GoRout to alert the offense to shift into kicking formation and kick the extra point. If they saw a favorable matchup based on the defense’s alignment, they’d attempt the two-point conversion.

“We were able to complete two-point conversions at almost an 85% clip because of it,” Drach says. “So it did give us an advantage at times. It was definitely something that was really beneficial for us.”

The technology also sped up the game, which appears to be paramount not just for college football but for every sport in 2024-25. GoRout allowed teams to operate faster and more efficiently, cutting down on the length of games—but without teams running more plays, which, as a safety concern, is important to the NCAA. Across the Liberty League, only two teams ran more plays in 2024 using GoRout than without, and on average, the uptick was nominal, achieving a balance of game speed and play economy that facilitates on-field action and excitement without putting players at further risk of injury.

But perhaps the most critical takeaway from the experiment is that . . . the technology worked. Coaches sent in 3,680 plays via GoRout devices in 2024, while the company received only two customer service calls and reported no network or connectivity issues.

“Communication and information is power,” Drach says. “And if you can continue to streamline those processes, you’re going to see a much better product on the field.”

The future of college football

Will there come a day when coaches pull up formations on their tablets, select plays from a Madden-like video-game interface, and send individualized instructions to each player on the field with the push of a button?

That may be an over-implementation. However, some coaches and players believe the potential for GoRout’s technology isn’t far off. As the tech becomes more widely accepted and develops further, we will likely see individual college football players receive hot route or audible calls in real-time based on how the defense lines up, or linebackers get new blitz assignments based on an offensive shift.

“I think it can change a lot,” Union College quarterback Patch Flanagan says. “Almost every college team in the country is using signals from the sidelines, but this could eliminate that completely. It’s a more streamlined process, and as the technology keeps advancing, there comes a certain point where the opportunities become endless.”

The extent to which this tech can revolutionize the game will come down to GoRout’s innovation capability, and the NCAA’s appetite for integration.

The cost factor

Cost will also be a key factor—one that appears to favor GoRout.

The package provided for the Liberty League in 2024—10 player devices and two coaches tablets—costs teams roughly $8,000. Meanwhile, one Liberty League head coach, Daniel Puckhaber of St. Lawrence University, says that one helmet communications company quoted him $70,000 for the same number of devices. And GoRout’s package includes not only the devices but also the software and the encrypted, secure network, which is ready to use out of the box.

If GoRout’s tech can solve the NCAA’s security, scalability, and tech equity problems with coach-to-player communication, it will be difficult for the brass to reject wider implementation. And when the rules committee meets in February, the results of the GoRout experiment will surely be near the top of the agenda.

If the coaches have their way, we’ll likely see more of it, and soon.

“It’s helped our team become more competitive and organized

Connectez-vous pour ajouter un commentaire

Autres messages de ce groupe

Consumers are only just starting to feel pain from Trump’s Liberation Day tariff spree. Amazon

When Donald Trump returned to the White House in 2025, many in the tech world hoped his promises to champion artificial intelligence and cut regulation would outweigh the risks of his famously vol

The first 27 satellites for Amazon’s Kuiper broadband internet constellation were launched into space from Florid

There are so many ways to die. You could fall off a cliff. A monk could light you on fire. A bat the size of a yacht could kick your head in. You’ve only just begun the game, and yet here you are,

Former Tinder CEO Renate Nyborg launched Meeno less than two years ago with the intention of it being an AI chatbot that help

The most indelible image from Donald Trump’s inauguration in January is not the image of the president taking the oath of office without his hand on the Bible. It is not the image of the First Lad

Ernest Hemingway had an influential theory about fiction that might explain a lot about a p