What was the World Wide Web like at the start? Long before it became the place we think and work and talk, the air that we (and the bots) now breathe no matter how polluted it’s become? So much of the old web has rotted away that it can be hard to say; even the great Internet Archive only goes back to 1996. But try browsing farther back in time, and you can start to see in those weird, formative years some surprising signs of what the web would be, and what it could be.

In 1994, the modern Internet (which you always capitalized and sometimes called just “Internet”) was itself only 11 years old, mostly the domain of researchers and hobbyists and hackers and geeks, who used an array of globe-spanning services for communicating (email and Usenet newsgroups, in addition to local BBS and IRC) and for downloading files via FTP and for searching for documents and texts with services like Gopher and WAIS.

The Web was a relatively new addition to the mix that tied a few of these systems together, with a twist. Tim Berners-Lee, a scientist at CERN in Geneva, had built it in 1989 to organize the lab’s sprawling pool of physics research by combining three technologies he’d invented: a language (HTML), a protocol (HTTP), and a way to locate things on the network (URLs). Now, the Web was growing rapidly, in part because it was free. In April 1993, shortly after the University of Minnesota decided to charge licensing fees for servers that used its Gopher protocol, managers at CERN chose to put the Web’s source code in the public domain and make it available on a royalty-free basis. That opened it to anyone who wanted to set up their own server.

The Web was also increasingly popular because it was easy to use and to look at, and even relatively easy to make. Instead of navigating folder hierarchies and plaintext files, users could browse pages with clickable hypertext. Now, anyone who could use a keyboard and mouse could traverse cyberspace. And by January 1994, when then-Vice President Al Gore presided over a summit at UCLA to hail the possibilities of the new “information superhighway,” millions of people suddenly had a slick new ride.

This story is part of 1994 Week, where we’ll revisit some of the most interesting and confounding developments in tech 30 years ago.

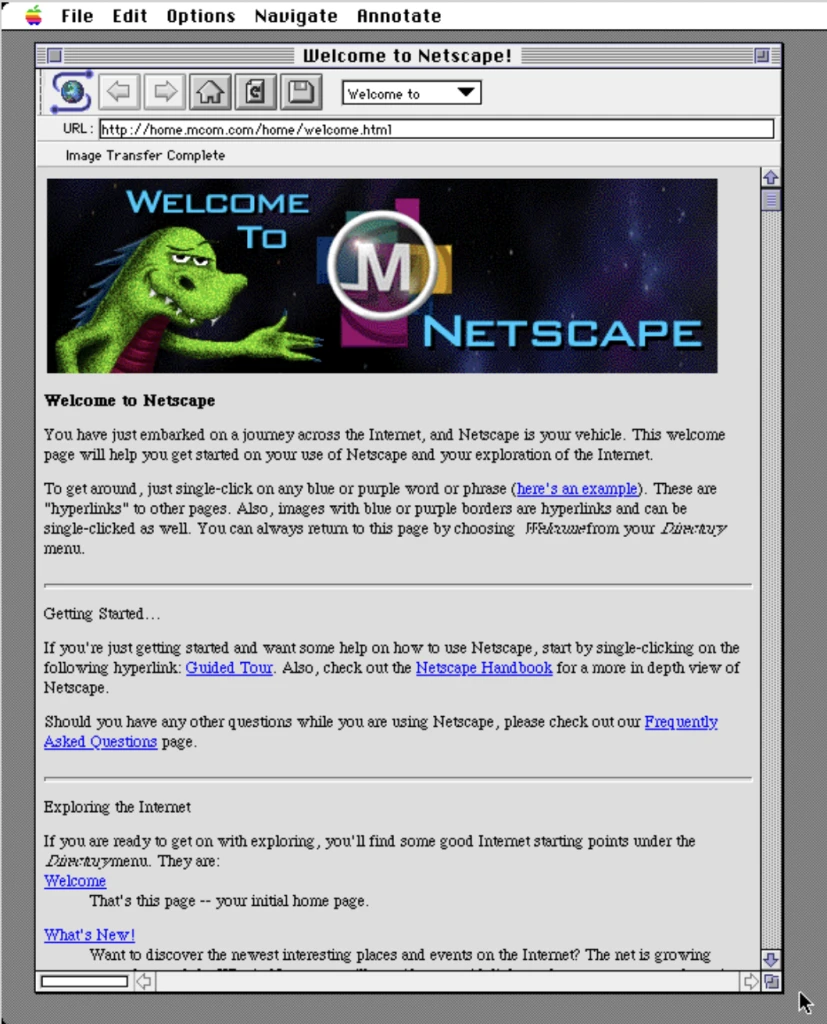

The previous year, Marc Andreessen, a fresh graduate of the University of Illinois, released “Mosaic” together with Eric Bina, an engineer he’d met at the university’s National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NSCA). It was the first major “graphical” web browser, capable of displaying images within pages rather than requiring separate windows. In November, they ported it to Windows and Mac computers. Suddenly, out on the austere frontier of text-only how-tos (see the first Web page), researchers’ home pages, and community sites that spilled over from Usenet and BBS, colorful, eye-popping images began to appear. Mosaic was turning the internet into a new medium, what Berners-Lee called “hypermedia,” displaying a universe of information that had previously only appeared on interactive CD-ROMs like Microsoft Encarta. Unlike CDs, however, the Internet was never-ending and always changing. And increasingly, it looked less like a computer terminal and more like a glossy magazine.

By December, Mosaic was being called “the first killer app of network computing,” by the New York Times. (Gore deserves some credit here: it was ”the Gore Bill” of 1991 that led to the NSCA.) At first, “a few people noticed that the Web might be better than Gopher,” the internet engineer Bob Metcalfe said later. Then came Mosaic: “Several million then suddenly noticed that the Web might be better than sex.”

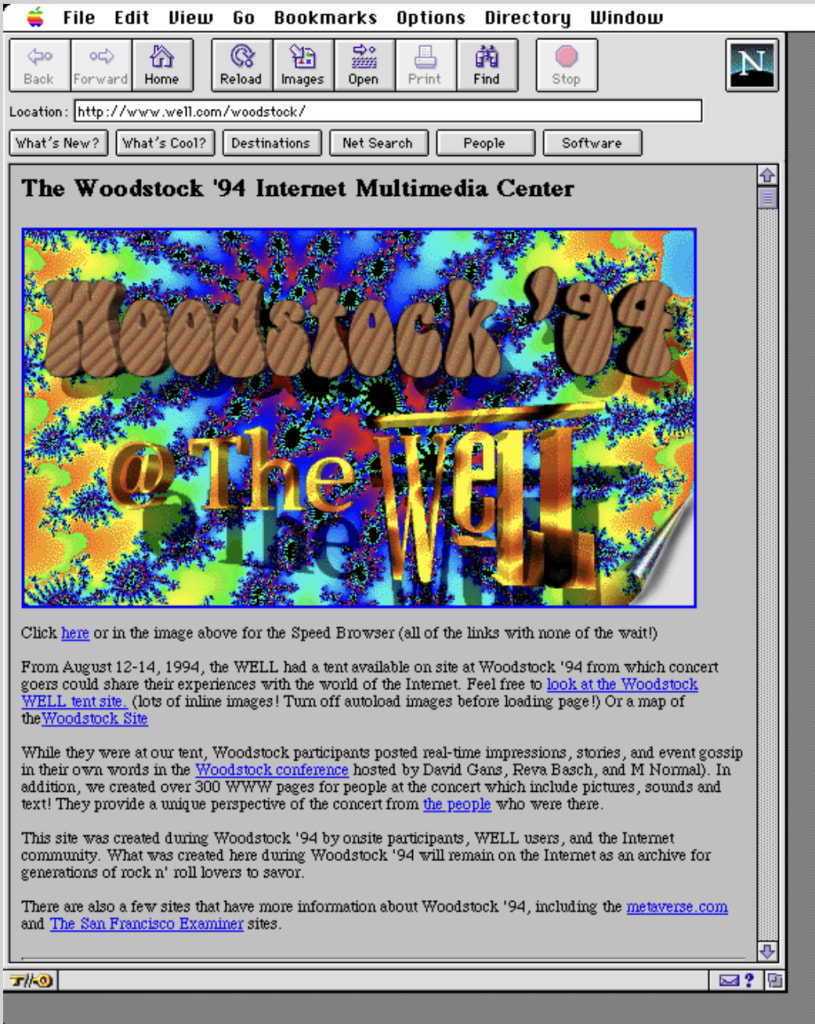

It was, CERN declared, “the year of the Web.” Throughout 1994, millions of PC users began venturing online for the first time, many of them with Mosaic. And for the many who dialed-in through the sanitized, cloistered portals of America Online (AOL), Prodigy, or Compuserve (all of which would offer their users web browsers by the end of the year), the Web was a revelation. By the time of the first World Wide Web Conference in May 1994—an oversubscribed gathering in Geneva that some dubbed “the Woodstock of the Web”—it was already too late to clarify: “the Web and the Internet are now often thought of as synonymous,” one attendee observed. Two months later, “The Internet” would land on the cover of Time.

It’s hard to say precisely when things changed online. Many point to September ‘93, when AOL users first flooded Usenet. But the web entered a new phase the following year. According to an MIT study, at the start of 1994, there were just 623 websites. By year’s end, it was estimated there were at least 10,000, including Yahoo!, the White House, and Snopes. The number of servers globally was doubling every two months. No one had seen growth quite like that before. According to a press release announcing the start of the World Wide Web Foundation that October, this network of pages “was widely considered to be the fastest-growing network phenomenon of all time.”

As the year began, Web pages were by and large personal and intimate, made by research institutions, communities, or individuals, not companies or brands. Many pages embodied the spirit, or extended the presence, of newsgroups on Usenet, or “User’s Net.” (Snopes and the Internet Movie Database, which landed on the Web in 1993, began as crowd-sourced projects on Usenet.) But a number of big companies, including Microsoft, Sun, Apple, IBM, and Wells Fargo, established their first modest Web outposts in 1994, a hint of the shopping malls and content farms and slop factories and strip mines to come. 1994 also marked the start of banner ads and online transactions (a CD, pizzas), and the birth of spam and phishing.

“I think the market is huge,” Martin Nisenholtz, an advertising executive at Ogilvy & Mather, told Time. Among his guidelines for marketing to the Net: “Intrusive E-mail is unwelcome.” Also: “It’s O.K. to post an ad for a used computer, for example, in a newsgroup called comp.system.mac.wanted, or to sell flowers in a corner of the Net marked florist.com.” (Fast forward to 2023, and spending on programmatic advertising globally was estimated to reach more than $300 billion; in 2021, a Comscore analysis estimated that $1.62 billion of that was spent on websites pushing misinformation.)

By the end of ’94, Andreessen and Bina would trade the university for Silicon Valley, launch Netscape, and release a new browser called Navigator. After a tussle with NSCA over the name, the browser’s internal code name—and eventual mascot—was the “Mosaic killer,” or Mozilla. (The name lives on: In February 1998, a year before its acquisition by AOL, Netscape released the source code for the browser and created the Mozilla Organization to coordinate future development; in 2003 the Mozilla Foundation was established to continue independent work on a new browser, called Firefox.)

Netscape Navigator, free and wildly popular, easily slayed Mosaic, bringing millions more Windows and Mac users onto the Web over the course of 1995. And it would set Netscape up for an IPO that August, then a highly unusual move for a company that had no profits. The startup ended the day worth $2.7 billion, launching the browser wars and a gold rush that, despite one dot-com bubble, hasn’t really stopped.

But back in ’94, the salesmen and oilmen and land-grabbers and developers had barely arrived. In the calm before the storm, the Web was still weird, unruly, unpredictable, and fascinating to look at and get lost in. People around the world weren’t just writing and illustrating these pages, they were coding and designing them. For the most part, the design was non-design. With a few eye-popping exceptions, formatting and layout choices were simple, haphazard, personal, and—in contrast to most of today’s web—irrepressibly charming. There were no table layouts yet; cascading style sheets, though first proposed in October 1994 by Norwegian programmer Håkon Wium Lie, wouldn’t arrive until December 1996.

“The appearance of websites was mainly influenced by the technological possibilities of the time,” says Petr Kovář, founder of the Web Design Museum, whose exhibited Web pages begin in 1991, when Berners-Lee put up the first one. “The Internet connection was very slow at that time and the websites therefore contained a minimum of graphical elements, with the emphasis being mainly on textual information. The typography was limited to the basic font sets that the user had installed on [their] computer and mostly a footer font prevailed. The navigational structure was generally simple and the user progressed linearly from one page to the next.”

Of course, at 14.4 kbps, it could take a minute to download a large image; in September, a new kind of modem would double connection speeds, from 14 kbps to a blazing 28.8 kbps. Until the arrival of 56K modems in the late ‘90s and commoditized broadband around the turn of the century, bandwidth was a frequent issue for early Web surfers. In Mark Butler’s How to Use the Internet, one of a number of guides published in ’94, the single chapter about the Web notes that “you may have to wait a long time to receive a document, or, in some cases, you may not even be able to make a connection.”

The fickleness and sluggish speeds and the modem’s loud ">dial-up whistles: These lost markers of the early Internet suggest a time when our information superhighway was little more than a humble country road. The highways and megalopolises would come later, courtesy of some of the world’s biggest corporations and increasingly peopled by bots, but in 1994 the internet was still intimate, made by and for individuals. Even such corporate like Microsoft’s were managed by a single person. Soon, many people would add “under construction” signs to their Web pages, like a friendly request to pardon our dust. It was a reminder that someone was working on it, another sign of the craft and care that was going into this never-ending quilt of knowledge.

Signs like those can be hard to find on today’s internet. As the web slides into a new period of decline—warped as it’s become around platforms and profiteers and propagandists, polluted by the scrapings and regurgitations of bots and spam and slop and slime—there’s a growing push to return to the principles of the old days. Beyond nostalgia, there might be something useful about looking back at the baby Web when it was still the Next Big Thing. What screenshots we can still get are like windows into an alternate world. Look in and think about how and why this web grew the way it did, and what could have been. Or try to imagine what life was like when the web wasn’t worldwide yet, and no one knew what it really was.

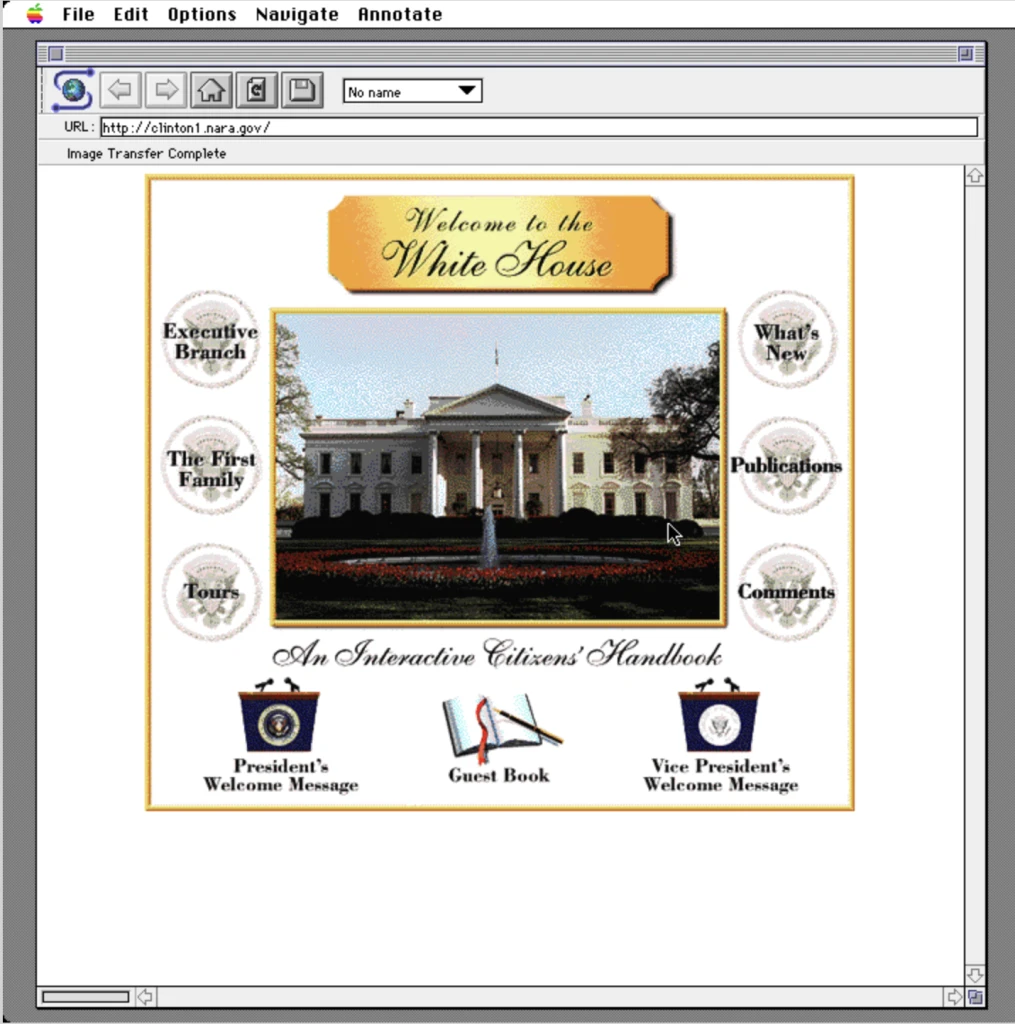

Whitehouse.gov

The Clinton administration had come to the White House with big plans for the “information superhighway,” but no one had thought much about setting up a Web page. Then, in November 1993, the White House purchased a costly T1 line—a dedicated connection to the internet via DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—and Jack Fox, the White House IT director, wanted to know what they were going to do with it. He posed the question one morning at a meeting of aides and executives, including Anthony Rutkowski, a representative from Sprint, which had the T1 contract. There was a long pause.

Finally, Rutkowski—inspired by his family’s recent visit to the White House—put an idea on the whiteboard for a basic “virtual tour.” Everyone liked it. Except, it turned out, his bosses at Sprint, who saw no reason why the telecom giant should start building websites. Rutkowski got to work on a home workstation. “Images from the guidebooks my father had purchased were scanned, and an initial prototype website was created,” he recalled in a 2020 essay. “My young daughter Kelly contributed to the design, insisting that any White House site had to feature Socks the cat.”

Zaloguj się, aby dodać komentarz

Inne posty w tej grupie

Former President Donald Trump called for the criminal prosecution of Google over what he said was the tech giant’s bias toward his presidential opponent, Vice President Kamala Harris, in onl

Journalist Ken Klippenstein was deemed by X to have crossed a line when he shared a link to a dossier about Ohio Sen. JD Vance. That has resulted in a ban from the social media platform, and promp

In the high-stakes showdown between the world’s richest man and a Brazilian Supreme Court justi

“So no one else uses chatgpt as an unpaid therapist?” TikTok user Ash Donner asks in a video. While her friends seem shock

Federal regulators who say Google holds an illegal monopoly over the

In 1859, Charles Darwin unveiled a theory of Evolution that shook the scientific world: the survival of the fittest, where nature thrives on ruthless competition and efficiency. This dog-eat-dog a